Yes, I said that I’d finished reprinting older pieces…turned out I hadn’t (although I think that this will be the last one). I circled around Los lunes al sol on multiple occasions on the old blog – mainly in relation to a half-seen connection between Bardem’s performances in this and Biutiful, which I was never able to fully articulate. Whatever I thought I’d seen disappeared on subsequent viewing and my dislike of the latter film stopped me from making an effort to return to the topic when I hit the buffers. But it caused me to revisit Los lunes al sol, which I had last watched while completing my PhD (it is one of the key films in my thesis). As I wrote a month or so before I published the analysis below:

You develop a funny attachment to films that feature in your thesis. Not all of them (there are a few that you’d have to pay me to watch again), but I think certainly the ones that find themselves woven into the fabric of your central argument; you are infinitely aware of their defects and flaws (you’ve pored over their minutiae for months, taking them apart and holding them up to the light), but you bristle slightly if someone else points them out. But once you’ve submitted, the idea of revisiting one of those films (for enjoyment!) doesn’t appeal; it’s difficult to view those films from any other perspective than the one through which you wrote about them in such detail. But this is where the funny attachment comes in for me because there are some that I nonetheless regard with what can only be described as affection, of which Los lunes al sol is one. There is something about the film that moves me no matter how many times I watch it, or how I’ve dissected it in the past: it is a film about solidarity, loyalty, about people being stronger together, and about how friendship can keep you afloat in the worst of times. Much of this centres on Bardem’s character, Santa, the pillar of a group of friends laid low by unemployment. If I were told that I could only watch one Bardem performance again, this is the one I would choose; in part because it is a perfect encapsulation of what ‘Javier Bardem’ and his star image mean within Spanish cinema, but also because I personally think that he has yet to better this performance.

Rereading the scene analysis recently, I was reminded of something that had stood out in a group of films I watched last year – when I had my mini Francesco Rosi season, one of the elements of his filmmaking that really caught my attention was how his framing of a scene (where the camera is positioned, how/where it moves, where/how the actors are positioned/move within the frame) visually represented the power dynamics within a group of characters and how that dynamic changed within the course of a given scene. This manner of imparting information – giving insight visually, in a way that can be read unconsciously by the viewer – seems (to me) relatively rare in contemporary cinema, which is all too often sloppily shot and edited, seemingly without a deliberate, thought-out rationale behind the choices made. Contemporary directors who do think about these elements include David Fincher, Steven Soderbergh, and Enrique Urbizu (I would like to write about the latter’s thrillers through his framing at some point) – all filmmakers who see (and represent) moving images in layers. Part of the richness of Los lunes al sol is that Fernando León de Aranoa had evidently given a great deal of thought to the group dynamics of this set of men and manages to fold those dynamics into his visual construction of a scene, as exemplified by the scene discussed below. I have only made a couple of edits to the text (originally published in October 2013) – instances where my original wording lacked clarity or was in some way confusing, and in one case to correct my Spanish.

Sequence: the argument in the bar, 01:15:51 – 01:22:32.

Los lunes al sol / Mondays in the Sun (Fernando León de Aranoa, 2002) was Javier Bardem’s return to Spanish cinema after a three-year absence from Spanish-language films, during which time he had made Before Night Falls (Julian Schnabel, 2000) and achieved his first Oscar nomination. Three years after mass redundancies caused by the closure of Spanish shipyards, the narrative follows three former steelworkers and their differing responses to unemployment: Santa (Bardem), José (Luis Tosar), and Lino (José Ángel Egido). While the film’s reception in the critical arena was generally positive (especially when Bardem is the focus), it has also received a more mixed response elsewhere: essentially, those who judge the film as formalists (the position taken by many film critics) see the film more positively than those cultural commentators (such as Quintana (2005) and Fecé and Pujol (2003)) who think that the film does not go far enough in its social commentary and who seem to judge the film by different criteria (i.e. their prescriptive ideas of what ‘Spanish cinema’ should be).

Aside from looking at how his role/performance coalesce with his star image (I think that exploring the issues of class and politics bring up some interesting issues in this context), there are a number of angles one could take in approaching Bardem’s performance in Los lunes al sol: for example, the madrileño performing a (deliberately vague – León de Aranoa didn’t want to specify location and filming took place in both Vigo and Gijón) northern accent as Santa. The film is notable for being the first (other than Before Night Falls) in which he performs an accent markedly different to his own (see E. Fernández-Santos (2002: 41)). But although I can hear that the accent he performs is not his own, I would have difficulty articulating exactly what it is he does vocally. So, for the purposes of this piece, I’m going to look at Bardem’s skill at ‘registering psychological and dramatic fullness through non-verbal representation’ (Perriam 2003: 102), effectively representing a character’s interiority externally through glances, posture, movement, and his sheer physical presence, and how that becomes an intrinsic part of his performance as Santa.

In my opinion, there are three scenes in the film that best illustrate Bardem’s performance and the essence of who his character is: the courtroom scene; the bedtime story; and the argument in the bar. I’m going to look at the last of those because it’s the longest of the three (and at 7 minutes, it’s also the longest scene in the film) and distills many of the film’s key themes whilst also giving the clearest sense of how these characters relate to one another (and what their shared history is). I’ve switched back and forth between English and Spanish in terms of how I’ve recorded specific lines – that reflects how I wrote my notes.

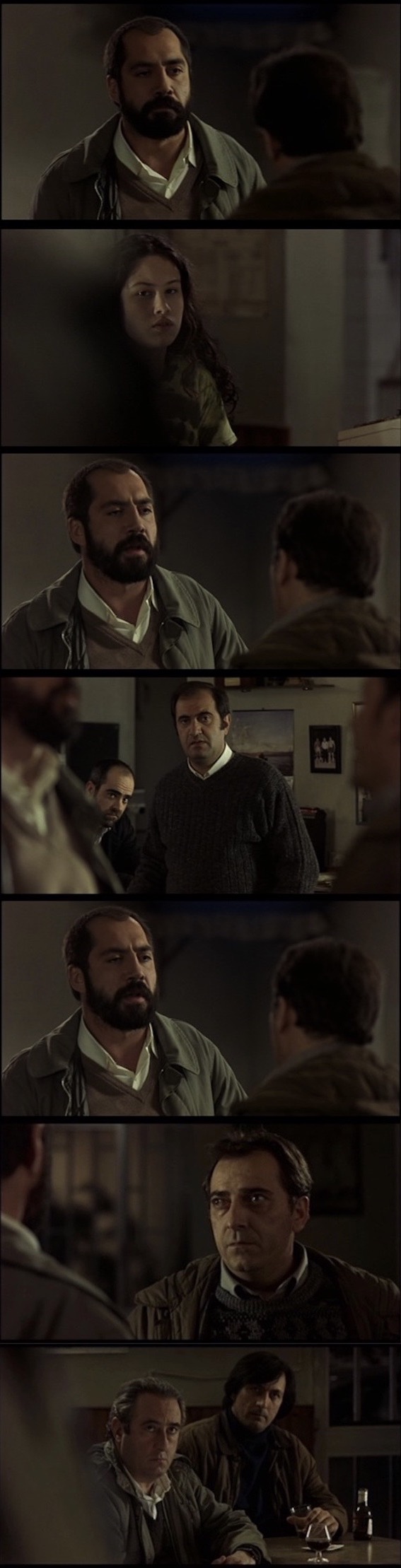

The position of the camera(s) in this scene is quite unusual insofar as it doesn’t respect the usual 180 degree line, mainly because of how the characters are arranged in the bar. In previous bar scenes, the camera has taken a variety of positions: near Amador’s seat at the end; behind the bar, not from Rico’s direct POV, but certainly from either his or Nata’s vantage point; and, when Lino was sitting there with Nata, from one of the tables by the door. But those sequences generally follow a shot/reverse-shot editing pattern; the camera remains static and we have a fixed sense of where people are in relation to one another (that most of the men are often standing at the bar usually allows them to be framed together). In this sequence, we still have this sense of where they are in relation to each other, but the camera angle cuts between several different positions (notably not from Amador’s angle, which foreshadows the significance of his seat being empty) and we never see more than a couple of the characters in frame together at a time (providing a visual illustration of how the sequence as a whole reveals the fractures within the group). Bardem / Santa is the axis for the camera: we don’t get his direct POV but his presence at the centre is integral to how we read the spatial relations (if he isn’t in shot, the eyelines of other characters or his voice pinpoint his location). Interestingly, it recalls the courtroom scene because the characters there are also seated in the round and the camera takes several positions, none of which strictly aligns itself with a character’s viewpoint.

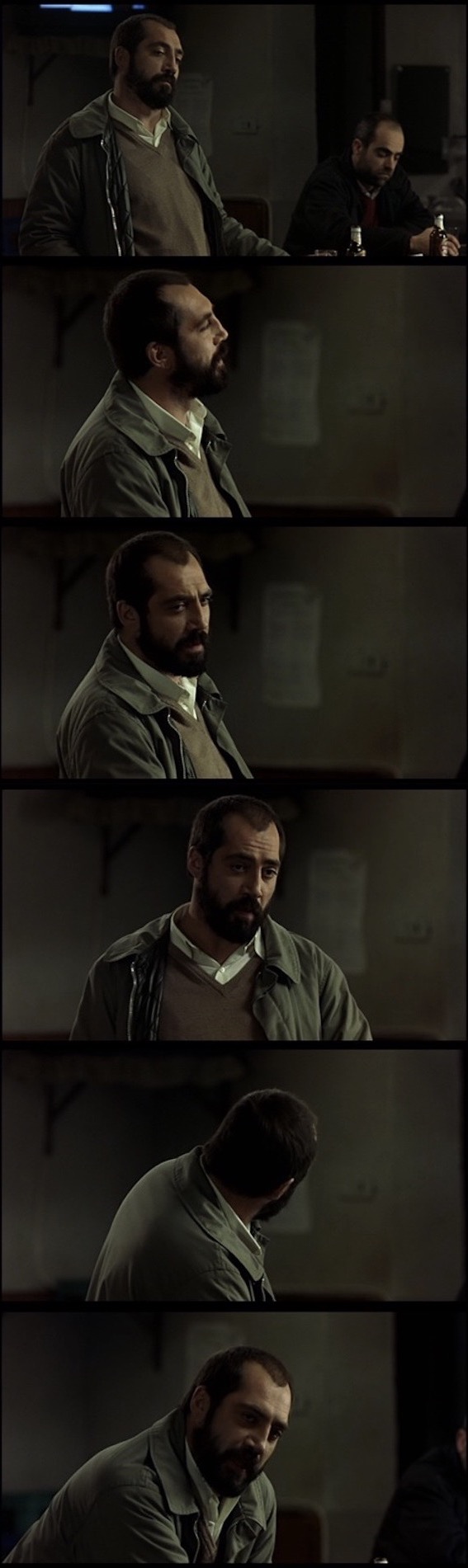

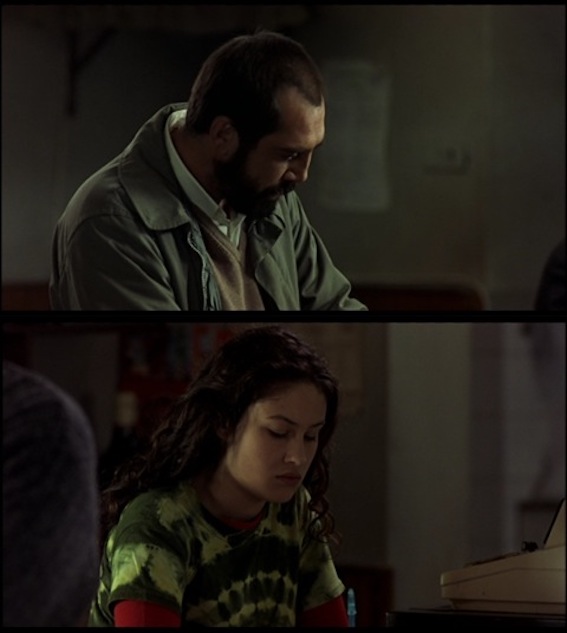

The scene starts with a black screen and the sound segues from the diagetic music in the previous sequence (where the music appears to come from the stereo in the solicitor’s car) to Reina’s voice in the bar. However the first image we see is not Reina (Enrique Villén) but rather the impact of his words on Santa. We see Santa in profile / slightly from behind (the angle does not match anyone’s POV), sitting at the bar so that Bardem occupies the left hand side of the screen – when Santa reaches for his drink (drawing attention to José (Luis Tosar) sitting around the curve of the bar), he fills both the horizontal and vertical length of the frame (he is the only character in the scene who consistently occupies so much of the frame).

To begin with, the sequence cuts back and forth between the far end of the bar where Reina is standing leaning sideways against the bar so that he is facing Santa, and Santa remaining seated and looking ahead (not at his interlocutor). It then starts intercutting Rico (Joaquín Climent) on one side of the bar (in front of Santa) and Lino (José Ángel Egido) and Sergei (Serge Riaboukine) sitting at a table (behind Santa) – there are now four angles in the mix, and the only person who appears in frame with Santa is José (who will be seen nodding in agreement with Santa during the argument – framing them together underlines their unity).

While Reina talks, we continue to get Santa’s silent, yet eloquent, reactions: Bardem’s posture, sitting, leaning forward with his elbows and forearms on the bar suggests that although Santa is pointedly not looking at Reina, he is in fact concentrating on what the man is saying. We can only see his face in profile, but the roll of his eyes and the way he tilts his head conveys both disagreement and a certain level of irritation (which is disguised by feigned amusement – Santa smiles, but it doesn’t reach his eyes) – we get the impression that this is not the first time Reina has espoused such views (and we have already seen tensions between the two men in an earlier bar scene, where Santa pours away a drink Reina has bought for him).

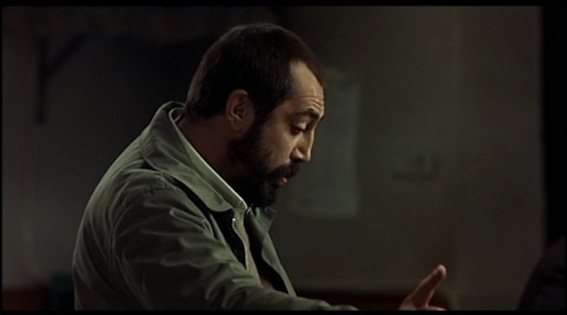

Santa’s first vocal interjection is signalled by his standing up, which is necessary because he is seeking to involve Lino in Reina’s criticism, and Lino is sitting behind Santa; in order to look at Lino, Santa either needs to swivel the chair around or stand and turn. The camera subtly moves with Bardem as he stands (it does the same with Reina as he moves later in the sequence but it feels even less pronounced then), keeping him slightly left of centre but with the bar top no longer in frame. Bardem arches his back, one of his methods of emphasising Santa’s weight, drawing attention to his paunch but also by natural corollary (his shoulders are also back) puffing out his chest – the alpha male in the room has just stood up. Juan Marsé describes Santa as ‘un parado que sobrevive entre la rebeldía interna y la desilusión, como un gorila entre las rajas del deprimente zoológico’ [‘An unemployed man who survives between internal rebellion and disillusion, like a gorilla between the bars of a depressing zoo’] (2004: 35), and there is something animalistic about the potential threat he manifests through his sheer bulk. He doesn’t fully face Reina at this point, looking at him sideways on with his head now tilted in a manner that could be taken as a challenge, but Bardem keeps his voice at normal volume with a neutral tone – that Santa is a threat to Reina in any way is only conveyed via his body language.

When Reina uses Rico as a positive example of what the men could have done after they lost their jobs, José starts to be intercut into the sequence on his own although he never moves from his seated position at the bar and continues to be shown in shot with Santa as well. I think his being shown alone is partly to show another fracture within the group but also to suggest his potential isolation. It is significant, given that he usually sits along the length of the bar where Santa and Reina currently are, that he is instead sitting alongside Amador’s (Celso Bugallo) empty seat; Amador serves as a warning as to where José might end up if Ana (Nieve de Medina – not present) leaves him. José’s scepticism as to the likelihood of everyone managing to do as well as Rico leads to Reina’s assertion “Not if you work hard”, which harks back to the bedtime story scene and by extension leads to an audience expectation as to Santa’s reaction. On cue, on that line, the camera cuts to Santa.

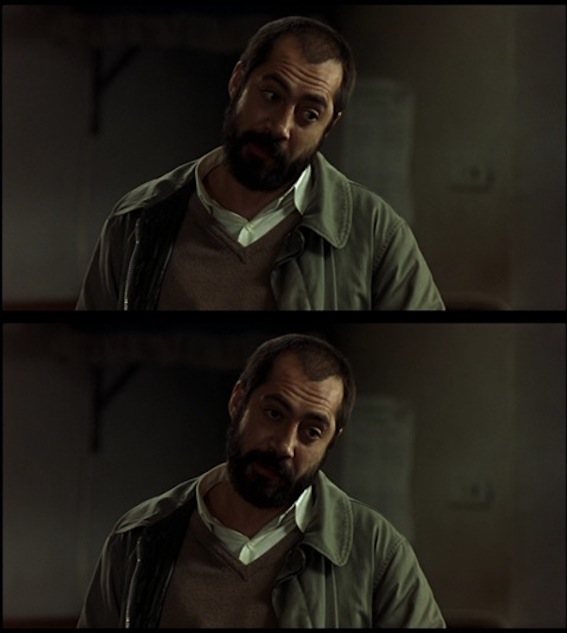

Bardem fills the left hand side of the frame, standing, leaning backwards, head tilted in a way that – in combination with his gaze – suggests that Santa is assessing Reina. When Reina mentions Amador, Bardem expels air through his nose in a snort that is somewhere between derision and disgust, and he looks away from Reina and down at the ground. Cut to Reina. Then cut back to Santa as he starts to speak. Bardem is now in medium close-up (head and shoulders) in three-quarter profile. His tone is no longer neutral and he is tilting his head down, so that he is looking up, giving emphasis to both his words and his eyes. As Santa starts to warm to his theme, Bardem shifts his weight between feet and changes his stance so that he is temporarily facing Reina straight on, in the centre of the frame. He stays centre frame when he turns his body back to the bar and keeps his head turned towards Reina / the camera as he speaks. However, as Santa begins to get angry, Bardem’s stance changes again and he leans with one elbow on the bar so that he turns away from Reina, with his back / the back of his head to the camera. Santa is trying to hide his emotions but it seems a brave decision by Bardem to hide his face; we feel the anger in the tightness of the angle of his neck and the stiffness of his shoulders rather than from a facial expression. When Santa turns back, he has both arms on the bar and is leaning diagonally into the frame, occupying most of the screen (again, emphasising Bardem’s size but arguably also the character’s centrality to the construction of the sequence – everyone else acts in reaction to him).

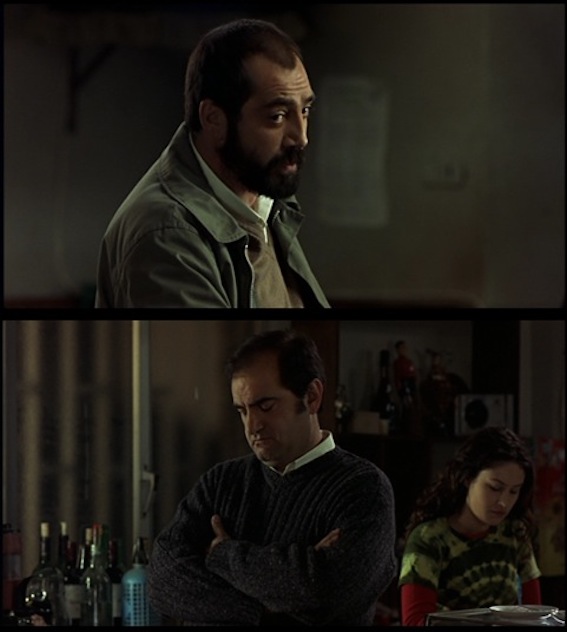

Cut to a reaction shot of Lino, which I think serves to emphasise Santa’s emotion at this point and how it has the potential to unsettle the other men. Throughout the film, Santa reveals himself to be astutely aware of the personal dangers faced by his friends and their currently precarious sense of self-identity (engendered by their lack of employment – as León de Aranoa puts it, ‘el trabajo es su capital, su única posesión, su bien más preciado; si se lo quitan, les quitan todo’ [‘Work is their capital, their only possession, their most valued asset; if it is taken away, everything is taken’] (Ponga, et al 2002: 158)), but he presents himself as the bluff pillar of the group; his showing emotion reveals that he is not unscathed by their common experience, and that seems to unnerve Lino. It’s noticeable during this part of the sequence that in each of the reaction shots, the other men are either looking down or away from Santa – lost in their own thoughts, but also finding it difficult to look at him given what he is talking about and how he is talking about it. Cut back to Santa – now upright and standing again – who starts to point and tap the bar for emphasis.

Up until now, Bardem’s gestures had been quite contained and had more to do with posture, but as Santa’s emotions come to the surface they become more expansive and his hands and arms more frequently come into frame. Still shot sideways on at the bar, when he now turns to Reina with his head tilted forward, eyes up, you get the sense of both Santa’s need to push and Bardem’s restraint. Cut back to Reina as he asks what the strikers achieved, and then back to Santa as Reina answers his own question with “Nothing”. Santa is facing the bar, head bowed, he turns as he says “Estabamos juntos” [“We were united”] with force and Bardem shifts his weight forward as if Santa is going to start moving in Reina’s direction. Reina looks away.

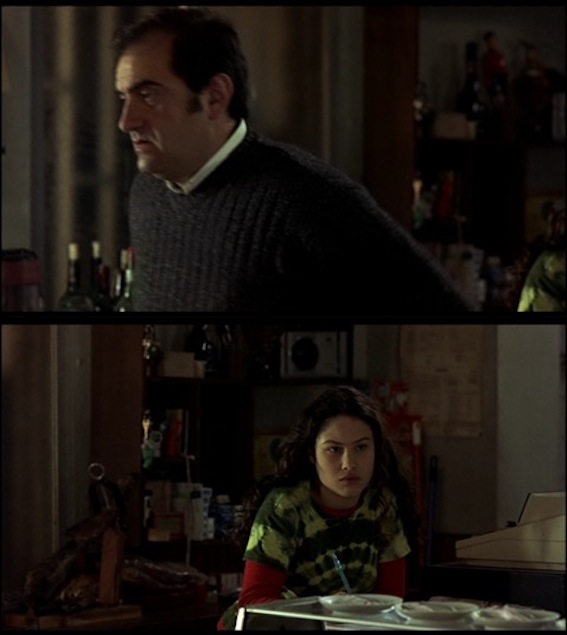

Cut to a shot of Rico, this time with Nata (Aida Folch) visible behind him (the first time we realise that she is present – the scene so far has been blocked in such a way as to hide her presence, despite her being in view of all of the men). But as Santa starts to talk about what went wrong with the strike, Bardem turns his back to the camera again (hiding emotion again, but this time a mixture of anger and sadness – indicated via tone of voice as well as his avoidance of eye contact).

Santa’s attitude towards Rico (Bardem tilts his head back, listening, his chin up but not in a challenge), as the bar owner justifies his actions during the strike, lacks the hostility he shows Reina, and he concedes the point about men who had families to take care of, again leaning forward and tapping the bar for emphasis. In response to Rico’s “There wasn’t anything else”, he gives an eloquent shrug, smiles with a nod, and says “Cojonudo” [“Brilliant”] twice (the second time half muttered), turning so that he is centre frame. He looks left so that his body is facing forward but his head is in three quarter profile, and then he turns back to the bar, his head bowed; it gives the impression that Santa knows this argument is going nowhere (it has effectively already been lost – what they’re arguing about happened three years earlier) but he can’t walk away from it and is therefore tethered to these people and a need for someone to acknowledge that what happened wasn’t right (hence his moving about on the same spot).

At this point Nata starts to be intercut into the individual reactions (now the sixth angle within the set-up – and the closest to being Santa’s POV), the first lone shot of her coinciding with a heavy sigh from Santa. That her individual reactions begin at a point when Santa’s words form the audio – rather than Rico’s (her father) – and that they physically occupy the same space within the frame (as shown above), speaks to the connection between the two of them (she is the only character capable of leaving him lost for words), but arguably also re-enforces Santa’s association with children; he is repeatedly shown interacting with them – the children of the two women we see him flirting with and the boy he babysits – and he is the only male character who does so. At this point, as Bardem shifts his weight again, Santa seems more weary and sad, although his pointing towards Amador’s empty chair (seen almost from Santa’s own POV) has an emphatic flourish, and he then starts to pick up speed again. [The manner in which Amador preys on Santa’s mind is revealed a couple of scenes later, when rather than leaving to meet a woman – as José presumes – Santa instead goes to check on the older man at home (and discovers his body)]

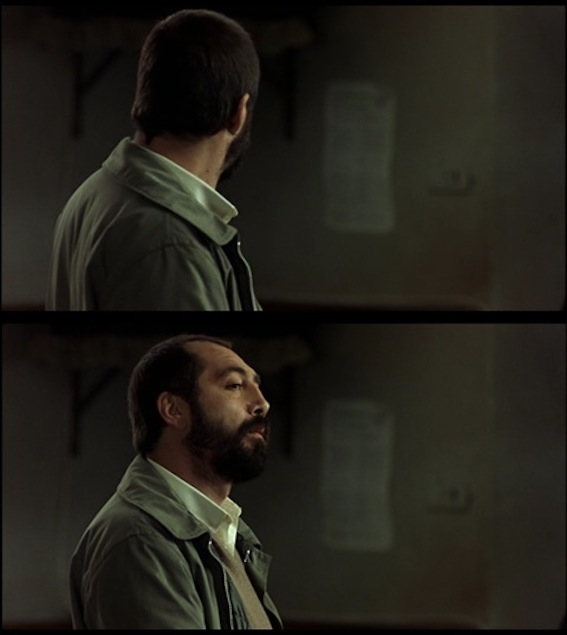

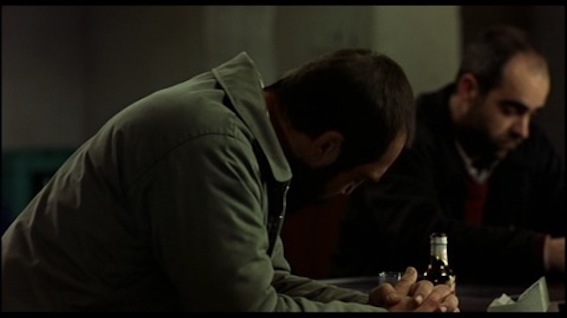

When he talks about ‘the agreement’ that divided the strikers he taps the bar with more force and his tone becomes more aggressive. Bardem now hunches his back forward, which makes him appear smaller (a physical representation of a sense of defeat), once more leaning into the frame towards Rico to emphasise what he’s saying (and also talking much faster). “We weren’t united anymore. They’d divided us.” He turns away again and looks down at the ground rather than directly at any of them; his tone of voice and stance here (looking down, more contained) speaks of disappointment, some residual anger, but mainly sadness, and it reveals more clearly that the group is still divided because of what happened three years earlier. At the end of his explanations as to how they each ended up in the positions they are now in, he looks directly at Reina, head back and chin up, defiant and issuing a clear challenge. The look in Bardem’s eyes when (in response) Reina argues that the shipyard wasn’t competitive enough and that he’d go to a different bar if the drinks were cheaper elsewhere is one of disgust and his upper lip slightly curls. He now properly raises his voice and bangs on the bar with his hand, speaking rapidly.

As Santa outlines his explanation as to why they wanted to close the shipyard (the site is by the sea and worth a fortune to property developers), Bardem looks away, turns back with a look of resignation and looks down while shrugging his shoulders and talking rapidly with an almost exasperated humour in his tone of voice. He then looks away (Santa possibly embarrassed at how much he is revealing of himself) again as he says, with one arm extended (calling attention), “Let me tell you something…I wouldn’t leave here even if they were giving the drinks away [elsewhere]”. He looks directly at Reina and then at Rico, “I’ve been here for three years and I intend to keep coming…even if you did sign the agreement” – a line that reveals his own sense of loyalty to these men but also the stock that he places in it as a quality (he is directly contrasting himself with Reina, who looks away). He sighs heavily and then turns to face Reina, standing centre frame, smiling as he fiddles with a napkin – “I could get a job serving drinks tomorrow. But if everyone gets laid off, there’ll be no customers”, his head tilted at an acute angle to the right (his gaze looking down and to the right), which places emphasis on what he’s saying but there’s also something slightly playful about it, “That pisses me off” (repeated, the second time as a mutter, as he looks directly at Reina).

He then turns back sideways on to the camera, head inclined forward. His voice is no longer raised but is still emotional – not a neutral tone – his voice catching on the line “You signed away your kids’ jobs […] We lost.” Close up of Nata on that line, then cut to José, who sighs and asks for another drink (subtly connecting José’s drinking to the defeat / losing of self).

The end to that part of the discussion is signalled by the camera panning (rather than cutting) to Nata as Rico crosses over to José. Cut back to Reina who decides to have another go.

Cut back to Santa, back to leaning against the bar in such a way that he fills most of the frame. Bardem stands upright with a sigh as Reina continues to push, Santa’s voice now tipping into both irritation and personal hostility. When the subject of Reina’s current job comes up, both men take a step toward each other and violence seems a real possibility; the tension is heightened by the editing, which first intercuts Nata casting a worried look in Santa’s direction, then Rico and José looking, then Lino and Sergei watching apprehensively, within the shot/reverse-shot of Santa and Reina’s exchange. This particular sequence of shots also reinforces Santa/Bardem as the axis of the scene and clearly delineates the spatial relations between everyone present (at no point during the sequence are all of the characters in shot). Bardem juts his chin out on the line “Un cabrón con pistola” [An arsehole with a gun] and pulls himself up to his full stature. The line about Reina’s wife (“She wanted me closer to her”) is said matter of fact but with a full glare maintained in their eye contact – Santa doesn’t repeat it (or retract it) when challenged and a heavy silence is allowed to hang.

Reina leaves. Santa sits back down, leaning forward on the bar, head down. Mutters “Gillipollas” [Dickhead]. Santa overstepping the line actually breaks the tension in the room (he is effectively back to ‘normal’) and – once Reina has gone – the other men visibly relax and their sense of humour reappears.

This scene occurs more than halfway through the film but – despite the tensions in the group being apparent earlier on (notably at the football match and the afore-mentioned scene where Santa pours away a drink paid for by Reina) – this is the first time we’re given a proper background as to exactly what happened at the shipyard; it becomes apparent that just as work has previously united them, it is also what currently divides them, whether in terms of their having found reemployment or simply in the different ways in which they’ve coped with its absence. León de Aranoa makes the point on the DVD commentary (which also features Bardem) that Reina isn’t a bad man, but the fact that he has found work separates him from his former colleagues. This is visually suggested in the framing: if you look above, you will see that Reina is always on the right of frame whereas the rest of them are on the left. The only exception is the family shot of Rico and Nata together – and Rico is often centre-frame part way between the two opposing sides – but the rest of the time even when in a group and they spill across most of screen, your attention is drawn to the left-hand side via either an actor’s movement of the depth of focus. The editing of the sequence also reinforces Santa’s status as the pillar of the group, a central point who is relied upon for his steadfast sturdiness. He reveals himself to have a far subtler (though firmly-held) take on the situation than Reina at the same time as he shows that he is unable to change who he is for the sake of an easier life (the sequence that directly precedes this one has already shown him to be a man who has to stick to his principles, albeit in a somewhat childish way in that specific instance). He is down but not out.

In terms of Bardem himself, the dichotomy between his powerful physique and the sensitivity he conveys with his eyes (on full display in this sequence) is something that was established at the start of his career (in the films he made with Bigas Luna), but his performance in Los lunes al sol serves as one of the best examples of his ability to convey complex psychological insight through subtle gestures and modes of behaviour. As I have said elsewhere, if you told me that I could only ‘keep’ one Bardem performance, this is the one I would choose.

References:

Fecé, J.L. and C. Pujol (2003) – ‘La crisis imaginada de un cine sin público’, in Once miradas sobre la crisis y el cine español, edited by L. Alonso García, Madrid: Ocho y medio, pp.147-166.

Fernández-Santos, E. (2002) – ‘”Mi mayor preocupación es el respeto al personaje”‘, El País, 24th September, p.41.

Marsé, J. (2004) – ‘Javier Bardem, un actor que inspira’, El País, Revista, 7th August, pp.34-35.

Perriam, C. (2003) – Stars and Masculinities in Spanish Cinema: From Banderas to Bardem, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ponga, Martín, and Torreiro (2002) – Hipótesis de realidad: el cine de Fernando León de Aranoa, Melilla: Consejería de Cultura de la C.A. de Melilla y UNED.

Quintana, Á. (2005) – ‘Modelos realistas en un tiempo de emergencia de lo político’, Archivos de la Filmoteca, no.49, February, pp.10-31.