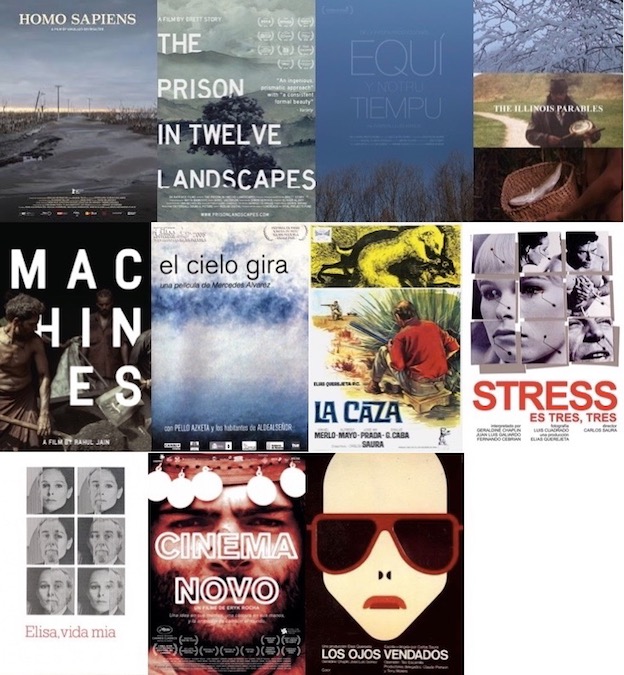

Director: Carlos Saura

Screenplay: Carlos Saura and Angelino Fons

Cast: Ismael Merlo, Alfredo Mayo, José María Prada, Emilio Gutiérrez Caba, Fernando Sánchez Polack, Violeta García.

Synopsis: Old ‘friends’ José, Paco, and Luis reunite after eight years for a day’s hunting, with Paco’s brother-in-law Enrique also enthusiastically tagging along. As the day wears on, old tensions become apparent and violence bubbles to the surface.

Link: My original post on the film, on the old version of the blog.

Generally considered Carlos Saura’s first masterpiece, La caza won the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival in 1966 (the director’s first international award) and is a landmark in Spanish cinema, one of the most representative films of what became known as Nuevo cine español [New Spanish Cinema]. It also marks a new stage in Saura’s career as the first of his collaborations with producer Elías Querejeta, and represents a stylistic leap on from Llanto por un bandido courtesy of Luis Cuadrado’s cinematography and the sharp editing of Pablo G del Amo (two members of Querejeta’s preferred team of technical crew).

Watching the film today – and cognisant of Saura’s continuous problems with the censor – it’s somewhat amazing that the film exists as it does. Set over the course of one scorching day as four men – former colleagues José (Ismael Merlo), Paco (Alfredo Mayo) and Luis (José María Prada), along with Paco’s brother-in-law, Enrique (Emilio Gutiérrez Caba) – hunt rabbits in the arid countryside. The film takes place in a location (specified in titles at the start of the film) that had been a battlefield during the Civil War, and ‘the war’ (the censors ensured that the Civil War is not explicitly mentioned) permeates the narrative and the relations between the men (the older three served together). Saura cannily employs the landscape as a metonym for the psyches of those who survived the war: battle-scarred, with secrets and remnants of violence hidden in darker recesses. In The A-Z of Spanish Cinema, Alberto Mira observes that the use of metaphor and strong imagery ‘went beyond narrative needs: the heat that drives characters to madness could be read in terms of the stifling atmosphere created in the country after the Civil War, and the butchery was easily read as a reference to the conflict itself […]’ (2010: 71).

For the most part the film is realist in its depictions, but frequent extreme close-ups of sweating faces (a technique that also signals how claustrophobically trapped each man is in his own behaviour), weapons and ammunition – and of rabbits in their death throes – ramp up the tension and give a slightly surreal edge to proceedings. It’s almost a ‘heightened’ reality, as if the camera is feeling the effects of that relentless heat. It feels like a very modern film, not just visually but also in our access to the interiority of the characters, conveyed through their private thoughts in voiceover and also in having them break the fourth wall in moments of honesty and confrontation (although talking to each other, they individually face directly into the camera as they speak). Likewise their states of mind – or at least the unspoken animosity under the surface – is signalled early on via the editing in the sequence where the men are preparing their weapons: a series of shot-reverse-shots show Paco in extreme close-up checking his sites facing right, then cuts to an extreme close-up of José doing the same but facing left (making it appear that they could be aiming at each other). The sequence of shots then repeats before a mid-distance shot establishes their actual positions in relation to each other (sitting alongside one another facing in opposite directions).

Saura’s use of the implicit includes the casting of Alfredo Mayo, who had a particular set of associations for contemporaneous Spanish audiences. As Marvin D’Lugo explains in his book on Saura’s films:

‘As a young man, Mayo built his career upon a series of forties films playing the role of the stalwart Nationalist hero fighting the Republican scourge. By far, the most influential of these was the role of José Churruca in Sáenz de Heredia’s Raza. Not only did Mayo play the part of the nationalist patriot; his role was fashioned as a sanitised version of the Caudillo, replete with narrative parallels to Franco’s own biography. Nowhere in [La caza] is there any overt reference to Mayo’s former screen persona, yet implicitly, the character of Paco seems to represent a sequel to the earlier Alfredo Mayo, film-actor-as-national-hero. It is a shattering statement of the passage of time and the transformation of a bygone mythic hero into a venal and narcissistic old man.’ (1991: 57)

In contrast, as an outsider to this clique – and crucially of a younger generation – Enrique is at one remove from the associations generated by the older men. He therefore acts as witness, and audience proxy, when bitter resentments and disappointments finally cause a breakdown and the men turn on each other with spectacular violence. The film ends with a freeze frame of his face in profile – his panting still audible on the soundtrack – as he runs from the scene in horror.

References:

D’Lugo, M (1991) – The Films of Carlos Saura: The Practice of Seeing, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mira, A. (2010) – The A to Z of Spanish Cinema, Plymouth: The Scarecrow Press.