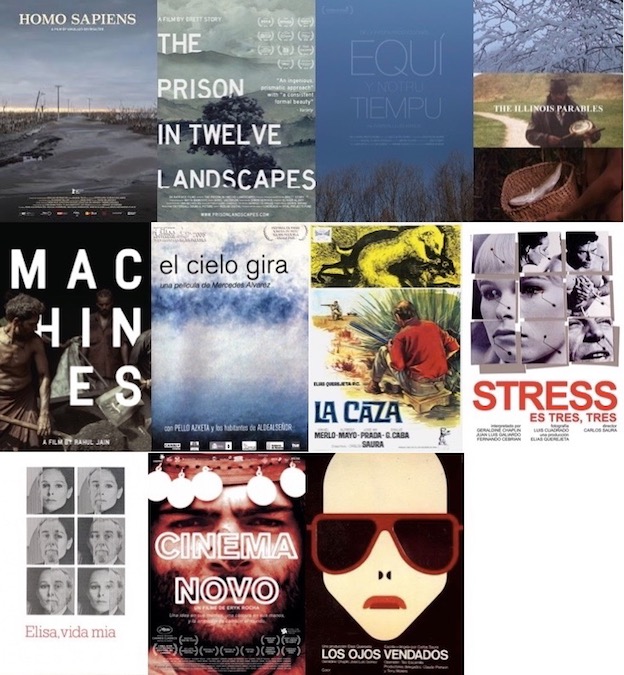

Director: Carlos Saura

Screenplay: Carlos Saura

Cast: José Luis Gómez, Geraldine Chaplin, Xabier Elorriaga, Andrés Falcón, Lola Cardona, C.E.T. actors (theatrical group).

Synopsis: Despite anonymous threats, a theatre director writes and rehearses a play based on the real testimonies of torture victims…and begins a relationship with a married woman.

The impetus for Los ojos vendados stemmed from two events in Saura’s life: he participated in the Bertrand Russell Tribunal, which documented evidence from victims of Latin American state torture; and his eldest son, Antonio, was beaten by a group of right-wing youths. The film’s protagonist – Luis (José Luis Gómez), an acting teacher and theatre director – is therefore positioned as a kind of proxy for the director. In the opening sequence he likewise sits on the panel of a tribunal publicly denouncing state torture, and finds himself unable to shake the words of one witness (the film’s title comes from her testimony) from his mind – in response, he writes and begins to rehearse a theatrical production based on the witness testimony heard by the panel, but receives anonymous threats warning him to stop what he’s doing (which he ignores).

This was brave subject matter to tackle during the Transition. Although censorship was technically finished at this point (my 2014 article on documentary and censorship during this era points out that the State could still disrupt and obstruct filmmakers in other ways), this period was the beginning of ‘the pact of silence’ – the consensus of the Spanish Establishment being that in order for the country to move on from the dictatorship, everyone needed to forget what had happened in the past. The balance of power within this obviously sits with the victors of the Civil War – the losing side had been silenced during the dictatorship, unable to publicly mourn their dead (in numerous cases not even knowing where the dead were buried), and were now being told to let sleeping dogs lie. In this febrile social context Saura chose to make a film in solidarity with victims of state torture, and which contains the implicit suggestion that the past is inescapable – via his recurring theme of memory, he shows that we carry our ghosts with us (as symbolised by Luis’s visions of coal dust – a reminder of another life – in the bathroom sink). Los ojos vendados therefore offers a continuation of Saura’s longstanding political focus, but also coalesces with his obvious interest in performers, their inner lives and creative processes.

If Luis is a loose proxy for Saura, Geraldine Chaplin’s character – Emilia – is in some ways a continuation of Elisa from Elisa, vida mía. Like Elisa, she doesn’t know who she is or what she wants to do with her life, and is distressed by her lack of purpose; her relationship with her husband (Xabier Elorriaga) fractures because of her attempts to find herself through artistic endeavour (by joining Luis’s drama workshops). When this results in domestic violence, she flees to Luis for help. But despite his understanding some of her angst – he also questions whether he has done anything of real worth in his life – their subsequent affair doesn’t alleviate her existential anxiety (although their danced mutual seduction/striptease is easily the most joyful sequence Chaplin has in any of Saura’s films). However, Luis guides her towards self-expression and – although Emilia seems too self-conscious to let herself go during the acting exercises – her vulnerability creates a point of connection with the part she plays in the production, and she becomes a different woman onstage (in the double sense of playing a part but also becoming a more certain version of herself).

Luis gives Emilia the role of the woman with mirrored sunglasses, the woman whose testimony inspired him to write the piece. Chaplin doesn’t play the woman in the opening sequence (although the woman has been deliberately anonymised by the glasses and headscarf) but as the woman’s words echo around Luis’s imagination, it is Emilia (or Chaplin, at least) who he sees in her place – and I think that there’s some deliberate visual slippage in these sequences. Different versions of the testimony are reenacted at different times during the film’s narrative (effectively because Luis can’t shake the testimony from his mind) – sometimes Chaplin/not-Emilia is dressed in casual clothes similar to those worn by the woman during her testimony (specifically jeans and a khaki jacket), but at others the figure in Luis’s imaginings is clearly Emilia (her hairstyle, make-up, clothes and jewellery mark out Emilia as a different social class to the other actors in the workshops and are specific to her within the film’s narrative world – e.g. we don’t see anyone else wearing the pearl necklace or trench coat – so these are deliberate markers of her identity). The witness testimony relates to Latin American countries (and although as far as I could tell none are specifically named, the woman with mirrored sunglasses speaks with an Argentinian accent) but to me the visual slippage/blurring posits two things: this happened here (Spain); and this can happen here again. The latter is perhaps a fear lodged in Luis’s subconscious by the anonymous threats (but also arguably relates to the attack on Saura’s son) – I’d have to watch the film again to work out whether Emilia’s clothes specifically appear in sequences that follow a threat arriving, or whether this is something that builds up as the narrative progresses – but the film ends in a series of violent events, giving credence to that unconscious fear.

This is an occasion where writing about a film has revealed more layers to me than I was aware of while watching it. I’d like to re-watch Los ojos vendados, not least because I saw it without subtitles and was aware that in a couple of instances (mainly scenes where Luis seemed to be talking about the past) whole conversations were unintelligible to me (a combination of poor sound and poor comprehension – if I can pick up the gist of the topic, it’s easier to follow), so I know that there were things that I missed. It seems to be one of Saura’s lesser-known works, probably due to availability issues (it doesn’t appear to ever have been released on DVD), which is a shame because the way in which it brings together many of the director’s favourite themes gives the impression of someone refining his vision of the world. It’s a densely-layered film, possibly deceptively so – you could probably watch it just on the surface and still get a similar overall impression, but there’s a lot going on in relation to performance and memory (and more besides) that I’ve barely touched on here.