This isn’t the normal introduction to my end of year cinematic round-up posts. I decided that to only write about films at the end of this particular year would represent an omission of some sort because my 2016 contained comparatively little cinema. I don’t subscribe to the current ‘worst year ever!!!’ hyperbole (on a personal level, this year falls way short of the nightmare that 2013 was for me) but it has been a wearisome and dispiriting twelve months, and something of a grind to get through. What is perhaps different about this year is that I don’t remember a time when so many people of my acquaintance (online and IRL) have collectively been brought low by the unfolding (inter)national dramas (e.g. the campaigns and results of the EU Referendum and US elections, nationalism and the Right on the rise seemingly everywhere, and the disparate voices of the Left finding fault with each other rather than seeking common cause). You would think that a sense of shared experience (or shared horror) would in some way be comforting, but I haven’t really found that to be the case (apart from knowing that if I am part of a social/political minority, it is still a sizeable one).

Social media can be a point of connection, news source, and method of organisation but it also amplifies misery to a sometimes overwhelming degree, wilfully misinforms, and acts as an echo chamber that presents a partial reality. Maybe you can counteract those limitations if you are aware of them, but I’m not sure. Feeling exhausted from the cycles of exaggerated outrage, incoherent anger and despair (and that was just me), I took an extended break from Twitter in the summer and felt better for it; more able to marshal my own thoughts and feel that I was constructively educating myself in subjects that I didn’t know enough about (I recommend this book as a starting point for understanding what’s going on in the UK, and these articles by Will Davies and Gary Younge are the best analysis I read in the aftermath of the referendum result). I didn’t manage to find an alternative source of news that was sufficiently as wide-ranging as Twitter can be, so that’s something I’ll still be looking for in 2017.

Several people in my Twitter timeline – in both June and November – said that they had woken up to find that their country wasn’t what they thought it was. But as those articles by Davies and Younge make clear, this wasn’t an overnight change (and for some people there wasn’t a change at all; they already knew what was there from lived experience) – the political fallout that we are living through was years (if not decades) in the making. The 2015 UK election result was recent evidence that a significant number of people are willing to ignore the damage done to the vulnerable in our society by a petty-minded and intellectually-stunted political class, just so long as it doesn’t impinge on their own standard of living. If a positive can be found in the events of this year, it is that injustice and inequality were made visible in a way that forced more people to look at and acknowledge what is happening…although a lot commentators have failed to change their respective scripts, and so are now overtly out of sync with what we’re watching. The challenge ahead will be to keep looking and not avert your eyes.

At an individual level, my year began with rumours of job cuts where I work. Sure enough, job cuts were eventually announced in May. I kept my job (my team was reduced and our morale generally depleted) but it doesn’t feel particularly secure, and I can only see further cuts on the horizon.

I stopped writing for other places in May. Partly because I wanted to concentrate on training opportunities that might improve my employment prospects, but also because in all honesty I could no longer see the point in continuing to write unpaid anywhere other than my own blog. The impetus for writing elsewhere was that my original blog only covered Spanish cinema and I wanted to explore a broader spectrum of films – I can now do that here. But it also comes down to how I should spend my time and money. If you can’t offset travel / accommodation costs for film festivals against being paid for what you write, you are effectively paying to work (and in my case doing so either in my ‘free’ time or on annual leave from my actual job – holidays that involve deadlines aren’t a proper break, and the resulting fatigue feels like a one-way ticket to mediocrity in all forms of work). Having used up my existing savings in relation to festivals in 2014 and 2015 – and taking into account the level of precarity that exists in relation to my job – I can’t sensibly afford to do that anymore. I attended the AV Festival in my home city in March, but apart from that my only film festival experience of 2016 was a daytrip to Leeds to catch Oliver Laxe’s Mimosas when it screened at LIFF in November. I’d like to go to at least one festival in 2017, but it will be in the capacity of leisure if I do so (and probably a daytrip).

All of this – the personal and the political – brought my mood down, and in turn (probably) led to a certain lack of enthusiasm for cinemagoing…although it should be noted that other factors include my continuing frustration with the programming at my local independent cinema and a couple of negative encounters with obnoxious audience members in the first part of the year. At the point of writing this (23rd Dec), I’ve seen 105 films this year (34 of which were shorts – short films are what I’ve most missed from not attending festivals) and only 9 of them in a cinema. In contrast, I saw 312 films (141 features and 171 shorts) in 2015 – that’s quite a drop off, and an indication of my general disinclination to watch or write about film in the second half of this year. On the upside, I’ve read a lot more books and have generally found other things to occupy my time and keep my brain active (mainly involving maths and computers, which is not something I thought I’d ever write)! I’m intending to take a substantial break from blogging at the start of 2017 because there are some more courses I’d like to do, but I also need to think through what I want to do here, and watch some films just for the sake of enjoyment. There are a lot of films I’d like to catch up with – the most obvious 2016 misses at the moment are Son of Saul and I, Daniel Blake (I didn’t feel up to watching them when they were on release) – and it’s quite a nice task to create a rental list using everyone’s end of year round-ups.

But anyway (finally), on to my favourite films of the year – divided into ‘new’ (films from 2015 or 2016 and watched for the first time this year) and ‘old’ (anything pre-2015). I haven’t done a top 10 because it felt a bit like making up the numbers – so I’ve got eight in the first category and five in the latter, with some additional honourable mentions. For the new films I’m generally allowing other people’s words to stand in for my own (I haven’t written any notes while watching films this year) by linking to pieces written by people whose writing I admire and articles that gave me insight into the film in question.

New:

1. Fuocoammare / Fire at Sea (Gianfranco Rosi, 2016)

1. Fuocoammare / Fire at Sea (Gianfranco Rosi, 2016)

A timely film about the humanitarian disaster on Europe’s doorstep in the waters around the island of Lampedusa, 150 miles south of Sicily. The film initially follows 12 year old Samuele (probably the most affable presence I’ve seen onscreen this year) around the island as he makes slingshots and listens to seafaring tales from his father. I was bracing myself for some kind of manufactured ‘meet-cute’ between the boy and rescued migrants but, as Rosi makes clear in this interview, part of the point being made is that these groups of people share the geographic space but occupy completely different worlds – so although a doctor acts as a bridge between the two communities, they do not overlap. The film roots itself in the island and then circles outwards, first with overheard distress calls, short sequences of rescue boats and helicopters scouring the sea, rescued people being checked over when they’re brought onto land, but getting ever closer to the deaths on the waters. When we finally reach the inevitable tragedy (one example of many – on the day I’m writing, the number of people who have drowned trying to reach Europe in 2016 has passed 5,000) it is difficult to watch but necessary to witness. If a film can be described as ‘humane’, that is what Rosi has compassionately created.

Olaf Möller at Film Comment

Michael Pattison at Indiewire

2. L’ accademia della muse / The Academy of Muses (José Luis Guerin, 2015)

2. L’ accademia della muse / The Academy of Muses (José Luis Guerin, 2015)

As far as I know, Guerin’s surprisingly funny ‘pedagogic experience’ hasn’t screened in the UK at all – I was keeping an eye out for it appearing at a festival, but to no avail. I finally watched it on Filmin a couple of weeks ago, but I’ll now be keeping my fingers crossed for a DVD with optional English subs to be released (certainly I’d want subs before I attempt to write about it in any depth) – although in some ways it felt appropriate to be watching a film that plays with language and meaning without the benefit of my mother tongue.

Cristina Álvarez López at Fandor

Antonio M. Arenas’s interview with Guerin at Magnolia

Nicolás Carrasco at desistfilm

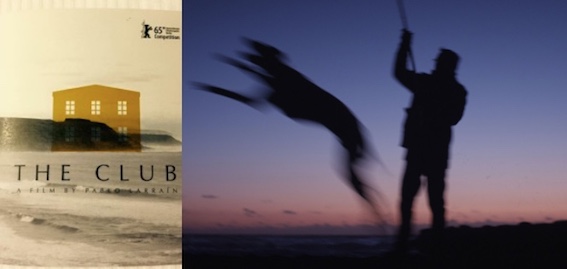

3. The Club (Pablo Larraín, 2016)

3. The Club (Pablo Larraín, 2016)

I have already made my admiration for Larraín’s work (and Alfredo Castro) clear. Expiation isn’t quite the right word that I’m searching for in relation to this drama because I’m not sure that atonement is pursued (self-interest dictates the actions of those who should be seeking it), but Larraín again exposes the ugly underside of Chilean society to shine a light on historical abuses of power that cannot simply be left in the past – they must be acknowledged because the repercussions reverberate into the present (the film’s gauzy, crepuscular light suggests that time may be running out – or perhaps that the old order are in their dying days). The Club also makes manifest the fact that dogs can make reprehensible people relatable. Larraín uses the relationship between Castro’s Father Vidal and the greyhound to foreground man’s inherent animality, and to highlight the absence of a certain level of humanity in this specific group of people. The contrast between what they acknowledge in relation to the dog (“Do you forgive me?” “No, motherfucker!”) and their lack of empathy for the abused man/child who appears at their door, is an illustration of their collective mindset and state of denial. A film that I will no doubt return to – but in the meantime, I’m looking forward to Neruda (Pablo Larraín, 2016), due for release in the UK in 2017.

Mónica Delgado at desistfilm

Nick Pinkerton at ArtForum

4. 13th (Ava DuVernay, 2016)

4. 13th (Ava DuVernay, 2016)

A cogently-argued indictment of institutionalised racism within America’s criminal justice system. The title refers to the 13th Amendment in the US Constitution – which states that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” – and DuVernay argues that slavery has effectively been maintained via that loophole of punishment, and turned into a profitable business for private companies. The film is impressively detailed in the breadth and depth of issues that it covers – rather than focus on only a few aspects of a complex set of interconnecting issues, DuVernay instead skilfully weaves everything together (prisons, courts, sentencing, legislation, government, private influence and vested interests) to create a multi-faceted overview, and tightly argued case, that alternately makes your blood boil or run cold.

Ashley Clark’s interview with DuVernay in Film Comment

5. Arrival (Denis Villeneuve, 2016)

5. Arrival (Denis Villeneuve, 2016)

The only film in this selection that I saw in the cinema – two of Villeneuve’s films were in my list last year, so I made an effort to see this one on the big screen. I don’t want to post spoilers as it is still in UK cinemas, so I’ll just say that a significant aspect of the last part of the film didn’t work for me but I’m also keen to see it again because (as with other Villeneuve films) where the film ends casts earlier events in a different light (it’s possible that a rewatch could resolve my problem with the film…or unravel the film entirely). It was nice to see a capable and intelligent female lead…and I badly needed a hit of cinematic wonder.

I’d advise against reading the articles below until you’ve seen the film.

David Bordwell on an aspect that I don’t feel able to name before you’ve seen the film

David Cairns at Shadowplay

Margaret Rhodes on how the filmmakers designed the alien alphabet

6. Tempestad (Tatiana Huezo, 2016)

6. Tempestad (Tatiana Huezo, 2016)

The VOD platform Festival Scope has two sites: one for film professionals (programmers, reviewers, filmmakers, and so on); the other is open to the general public and is increasingly being used to host selections from recent film festivals (a film can cost a couple of euros to watch, or sometimes it’s free but there are a limited ‘tickets’). I watched Tempestad on the latter when it hosted a number of films from Morelia International Film Festival because I had read about it in Neil Young’s article on Mexican female documentary filmmakers (see below), but also because it tangentially related to a book I had recently read, The Beast: Riding the Rails and Dodging Narcos on the Migrant Trail by Óscar Martínez (half price until the end of the year via that link). Martínez’s book is ostensibly about the migrants trying to make it to the US but that necessitates that he looks at violence in Mexico and the complicity between the authorities and the cartels. Huezo’s film comprises of testimony by two Mexican women, Miriam Carbajal (unseen) and Adela Alvarado, who have experienced the personally devastating consequences of that complicity in different ways: Miriam is a former customs official who was thrown into prison (controlled top to bottom by a cartel) when the authorities needed a very public scapegoat for a scandal (which she had nothing to do with); Adela is a circus performer, a nomad without a fixed home due to threats received (from both sides of the law) because of her persistence in searching for her daughter, who disappeared on her way to school a decade earlier. Powerless against the State and its agents, and caught within circumstances almost too nightmarish to comprehend, these two women regain some of their personal agency by telling Huezo their stories in their own words, with dignity and no small amount of courage. Huezo entwines word, image and a multi-layered soundscape into a haunting film.

Neil Young in Sight & Sound on the rise of female documentary makers in Mexico

The film’s website (includes a subtitled trailer)

7. Bella e perduta / Lost and Beautiful (Pietro Marcello, 2015)

7. Bella e perduta / Lost and Beautiful (Pietro Marcello, 2015)

Marcello’s film walks a line between fable and (unconventional) documentary, with a personable buffalo calf as one of its leads and a folkloric character as another, resulting in what Jonathan Romney has recently described as ‘a UFO of a film—in this case, an Unidentified Folkloric Object’.

Jonathan Romney in Film Comment

8. Baden Baden (Rachel Lang, 2016)

8. Baden Baden (Rachel Lang, 2016)

MUBI UK screened Lang’s feature debut alongside two of her earlier shorts featuring the same character, Ana (played in all instances by Salomé Richard). It was interesting to watch these close together as they form a kind of speeded up cinematic evolution of both filmmaker and actress. Ana’s sense of purpose (or lack thereof) changes with each film – it’s possible that these are different iterations of the character rather than an intended character arc across several films, but it’s also possible that these changes are a manifestation of Ana’s unformed self (she doesn’t know who she is yet – or what she wants to do with her life). It’s unusual to see a female slacker (several articles reference Frances Ha, but I still haven’t seen that (yes, I know), so can’t make that connection myself), or a female character granted the space to define herself, however unsuccessfully. It’s not actually the type of film I usually have much urge to see but I found this one charming and surprisingly moving – and Salomé Richard is a face to watch for in the future.

Honourable mentions (alphabetical): Embrace of the Serpent (Ciro Guerra, 2016) [review], Midnight Special (Jeff Nichols, 2016), Mimosas (Oliver Laxe, 2016), O Futebol (Sergio Oksman, 2015) [review], The Pearl Button (Patricio Guzmán, 2016), The Royal Road (Jenni Olsen, 2015) [VOD], Shaun the Sheep (Mark Burton and Richard Starzak, 2015), Spotlight (Tom McCarthy, 2015).

Old:

I reactivated my subscription to Lovefilm this year and have been more successful than in the past at watching the DVDs when they’re sent to me (rather than leaving them unopened for several weeks) – there are still a lot of older films that aren’t available via streaming, and a rental service has the advantage of reducing my impulse buys when I read about a film, actor, or director and want to watch them/their work. Overall the majority of the films I watched in 2016 were not from recent years – restarting the rental account allowed me to explore the work of filmmakers unfamiliar to me without committing to pricey boxsets.

1. Salvatore Giuliano (Francesco Rosi, 1961)

1. Salvatore Giuliano (Francesco Rosi, 1961)

I’m not entirely sure how I came to have a Francesco Rosi mini-season. It was possibly prompted by the re-release of his Tre Fratelli / Three Brothers (1981), which reminded me that I had Salvatore Giuliano and Le mani sulla città / Hands Over the City (1963) sitting unwatched on my shelf. I followed on with Cadaveri Eccellenti / Illustrious Corpses (1975), had to abandon an atrociously-dubbed version of Lucky Luciano (1973), and have yet to watch Cristo se è fermato a Eboli / Christ Stopped at Eboli (1978). My main frustration now is how few of his 20 films are available for home viewing in any format, and how even fewer are available with English subtitles (this seems broadly to be the case with Italian cinema in the UK – Rosi led me down a rabbit hole to Gian Maria Volontè and Elio Petri, and similarly very few of their films are available with subtitles). Salvatore Giuliano is my favourite of Rosi’s films so far and it wasn’t a surprise to find that Martin Scorsese rates it among his favourite films because he was who came to mind while I was watching it. They share an ability (for me, at least) to cause a sense of exhilaration through the sheer élan of their filmmaking – camera movement, editing, and sound are combined so that a visceral thrill comes from the form and style. Likewise both directors are interested in depicting the power dynamics within enclosed groups of men, but Rosi’s films also stand as critical portraits and indictments of aspects of Italian society. There were moments during Salvatore Giuliano where I realised that I was grinning from the enjoyment of watching something so well crafted. Henceforth I will be on a mission to locate more of Rosi’s films.

2. Modern Times (Charlie Chaplin, 1936)

2. Modern Times (Charlie Chaplin, 1936)

Cough – my first Chaplin feature – cough. I’m embarrassed that it has taken me so long to watch a Chaplin film in its entirety (I’ve definitely seen some of the shorts and various clips/sequences) but I’ll admit that I wasn’t expecting it to be so funny or so…modern. I am in the process of working my way through his features via Lovefilm.

3. Nightcleaners (The Berwick Street Collective, 1975)

3. Nightcleaners (The Berwick Street Collective, 1975)

My review of the film from the screening at the AV Festival in March.

4. Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray, 1955)

4. Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray, 1955)

Yet another admission of a chasm in my cinematic experience – I had never seen a Satyajit Ray film. The Apu Trilogy (which consists of Pather Panchali, Aparajito, and The World of Apu) is OOP in the UK but I’ve realised that when Amazon bought out Lovefilm they must have bought their back catalogue (which way back at the dawn of time used to belong to MovieMail when it was a rental business – I used to rent VHS from them through the post!), with the result that you can rent some titles that currently aren’t available to buy – including these three films. It is hard to separate them but I found something especially magical about this one – and I’m a sucker for depictions of sibling relations between brothers and sisters (a dynamic mixture of love and irritation).

5. Snowpiercer (Bong Joon-Ho, 2013)

5. Snowpiercer (Bong Joon-Ho, 2013)

“Know your place. Keep your place. Be a shoe.” A dystopian vision of the future in the aftermath of a climate-change experiment gone wrong, with the best and worst of humanity stuck on the same train. Depressingly plausible – as anyone who has travelled on British trains can confirm – but the violence is quite cathartic.

Honourable mentions (alphabetical – links take you to VOD versions where available): Daybreak Express (D.A. Pennebaker, 1953), The Friends of Eddie Coyle (Peter Yates, 1973), Güeros (Alonso Ruizpalacios, 2014), Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto / Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (Elio Petri, 1970), Land of Promise (Paul Rotha, 1946) [review], Spare Time (Humphrey Jennings, 1939) [review], Los Sures (Diego Echeverria, 1984), Utopias (Marc Karlin, 1989) [review].